Research progress of additive manufactured nanoparticle reinforced austenitic stainless steel by LPBF

-

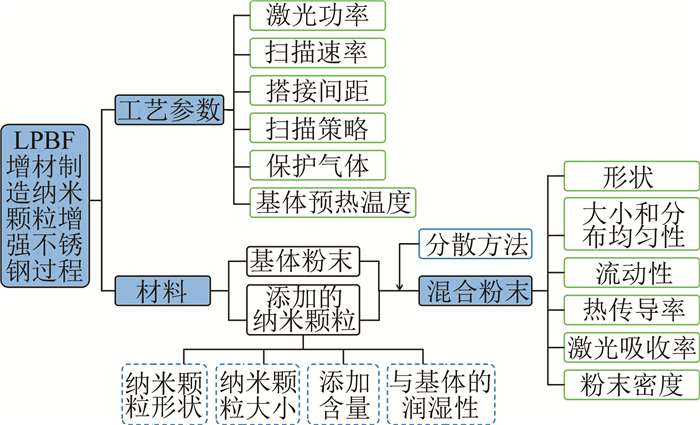

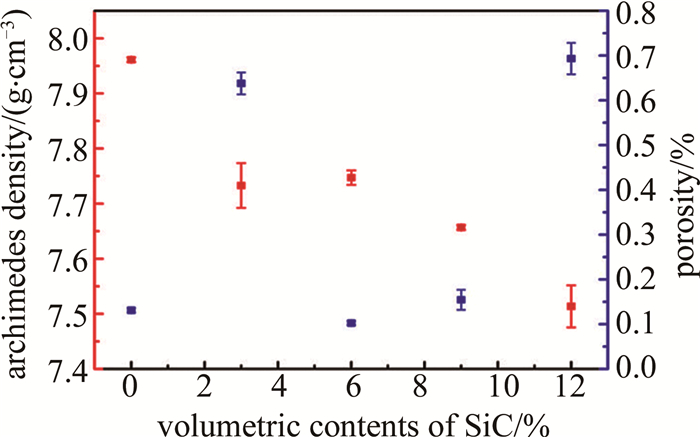

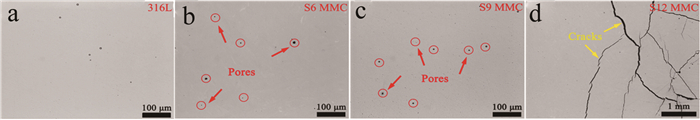

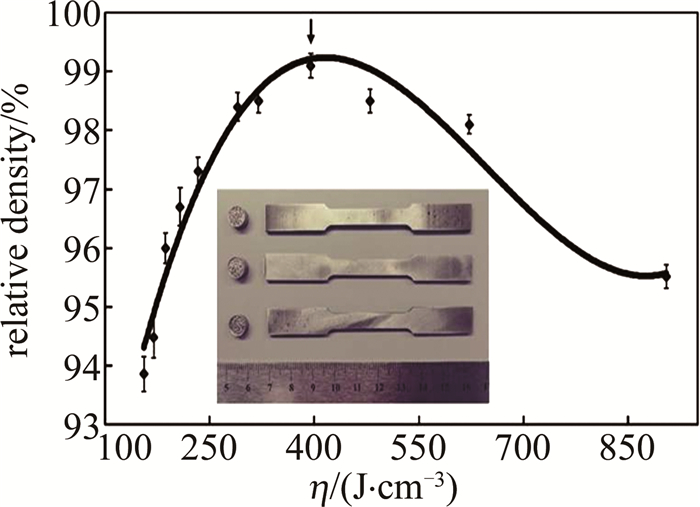

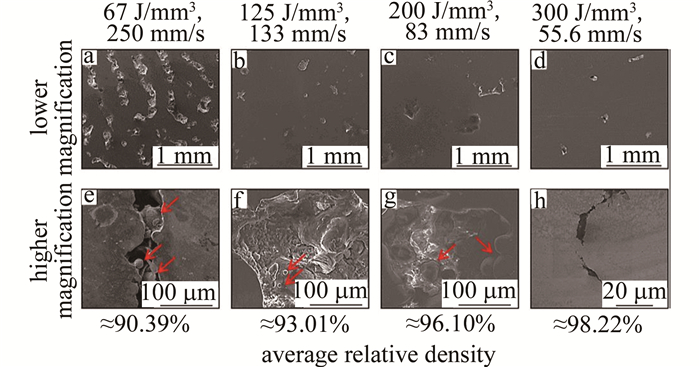

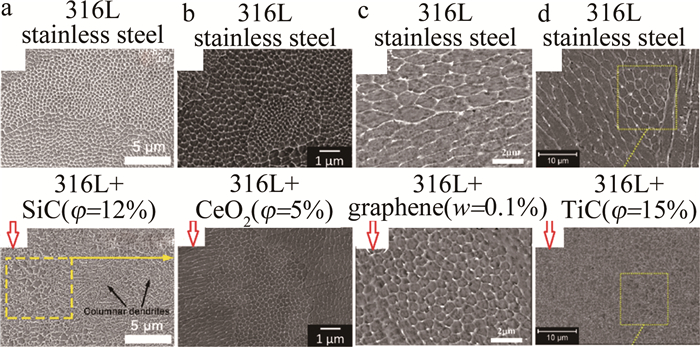

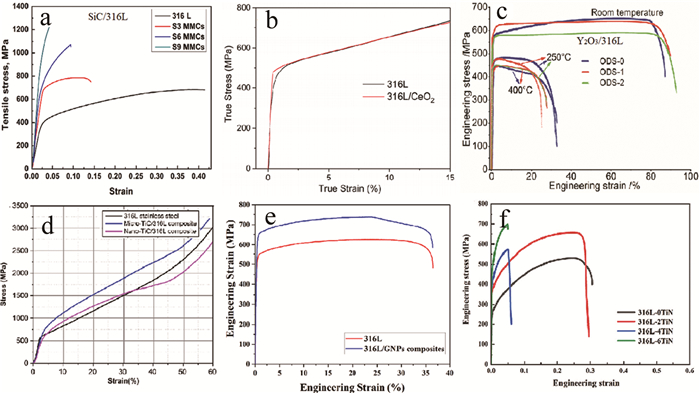

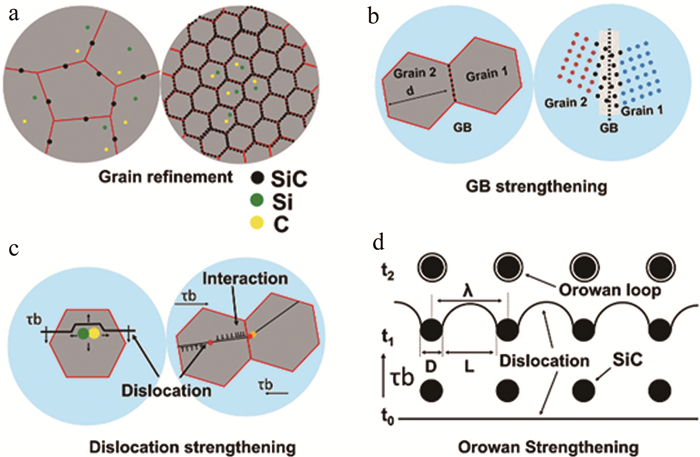

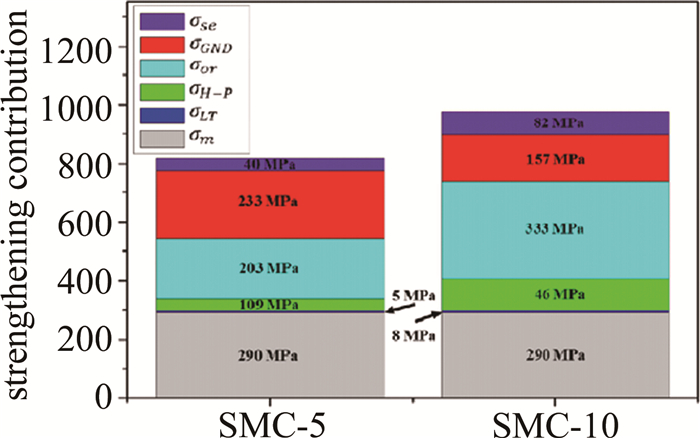

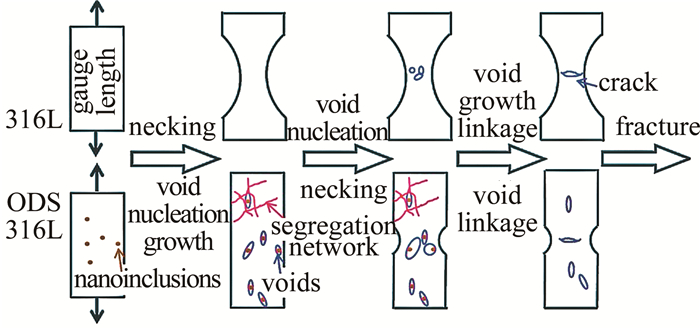

摘要: 激光粉末床熔融技术(LPBF)增材制造的奥氏体不锈钢因良好的可打印性和力学性能具有很好的应用前景, 但还存在一些问题限制其工业应用, 添加纳米增强相是调控其性能的有效策略之一。综述了纳米颗粒增强LPBF奥氏体不锈钢的研究进展; 讨论了纳米颗粒对致密度、微观结构和力学性能的影响, 并分析其强化机理。纳米颗粒的加入使复合材料孔隙率增加, 致密度下降; 胞状组织晶粒细化, 且具有较低的各向异性; 添加了增强相的奥氏体不锈钢在强度显著提高的同时还保持良好的延展性, 主要归因于晶粒细化、位错强化、Orowan强化以及载荷传递强化的综合效应。最后展望了LPBF增材制造纳米颗粒增强奥氏体不锈钢在未来需要进一步探索的研究方向。Abstract: The austenitic stainless steel additive manufactured by laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) has a good application prospect because of its good printability and mechanical properties, but there are still some problems that limit its industrial application. Adding nano-reinforcing phases is one of the effective strategies for regulating the properties of LPBF austenitic stainless steel. The review summarized the research progress of nanoparticles-reinforced LPBF austenitic stainless steel. We focused on discussing the effect of nanoparticles on the densification, microstructure, and mechanical properties. The strengthening mechanism was analyzed. Due to the addition of nanoparticles, the porosity of the composite material increased, and the density decreased. Cellular structure grains were finer with low anisotropy. Austenitic stainless steel added reinforcement phase not only significantly improved strength but also maintains good plasticity, mainly attributed to the comprehensive effects of grain refinement, dislocation strengthening, Orowan strengthening, and load transfer strengthening. Finally, the research directions of nanoparticles reinforced austenitic stainless steel by LPBF that need to be further explored in the future were prospected.

-

0. 引言

激光半自动制导是一种典型的激光制导模式[1],其基本原理是通过位于载机或地面的激光目标指示器发射激光束照射目标,由位于弹头的探测器接收目标漫反射的激光信号, 探测器通过对接收波门内多个脉冲回波的处理以实现对目标的捕获, 实现目标捕获后,通过对目标持续确认以实现对目标的跟踪。

其它激光目标指示器的散射信号和激光干扰机发射的信号都可能影响探测器的性能。前者是非恶意干扰,具有低重频干扰效果;后者通常工作在高重频工作模式,以保证干扰效果。干扰信号对探测器的捕获和跟踪环节都可能产生影响[2-3],具体的干扰效果与干扰机布设方位[4-5]、干扰信号重频[6-7]、干扰信号编码方式[8-9]有关,也与激光目标指示器信号波形[10]、探测器波门设计[11]、脉冲锁定技术[12]有关。

激光制导抗干扰的技术途径主要可以分为两种: 一是对指示器发射信号进行编码,提升目标回波信号信息熵,降低干扰信号与目标回波的相似性[13];二是在目标捕获和跟踪处理环节充分挖掘目标回波信号的特征信息,剔除不满足目标特征的干扰信号[14]。研究者深入分析了编码波形抗干扰技术,并分别提出了性能良好的随机编码波形和抗干扰算法[15-17]。WU等人[18]提出了基于接收波门临近回波的高重频干扰排查方法,改善了抗干扰效果。CHEN等人[19]提出了基于干扰重频估计的高重频干扰剔除技术,可有效对抗固定重频的高重频干扰。CAO等人[20]提出了一种自适应扩展实时波门技术,有效避免了干扰脉冲进入波门导致目标脉冲漏检的情况。

从原理上看,在满足激光目标指示器、探测器工程现实基础上,充分考虑感兴趣目标的行为特征和干扰机工作特点,开展发射波形精细化编码设计、脉间接收波门设计和抗干扰信号处理算法研究,可有效提升抗干扰性能。基于此,本文作者设计了一种随机重频发射信号,在收发准同步条件下,结合激光目标指示器、目标和探测器的运动特性,提出了端到端的基于自适应交叠波门的高重频干扰鉴别、目标探测方法, 仿真分析了该方法抗固定重频和随机重频干扰的性能。

1. 随机重频激光信号抗干扰模型

1.1 高重频干扰激光原理分析

探测器通过对特定距离上目标脉冲多个回波的连续探测实现目标捕获,并通过连续接收目标脉冲回波的连续观测实现目标跟踪。受激光目标指示器、目标和探测器运动影响,不同脉冲回波通常在时延上存在差异。为了有效实现脉间回波关联,通常设定与激光目标指示器、目标和探测器先验信息相关的具有一定宽度的距离波门。

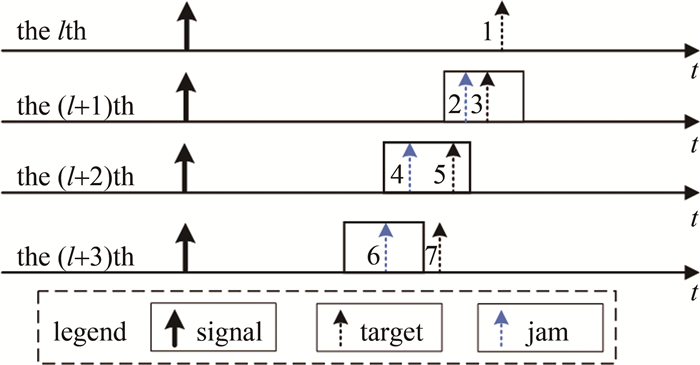

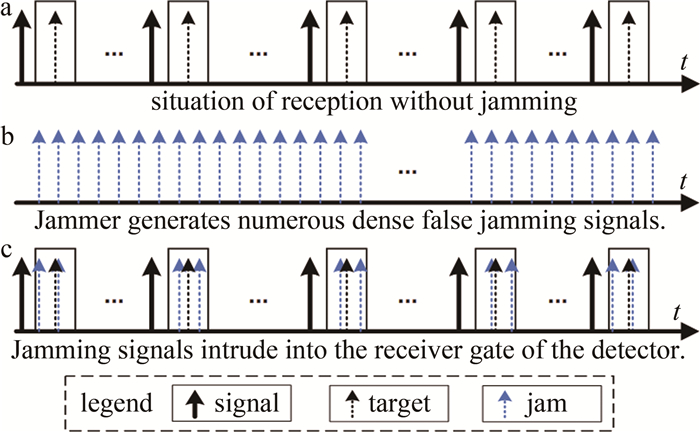

当特定波门出现连续脉冲时,探测器进入脉冲锁定状态,并通过对锁定波门内的回波连续探测的关联实现目标捕获。干扰机通过发射高重频干扰信号,在探测器上产生大量密集虚假目标信号充斥于探测器接收波门之内,以较高的概率打断激光雷达目标捕获跟踪链路,严重影响激光制导效能。图 1是高重频干扰的原理图。图 1a中给出了无干扰时探测器接收目标回波信号的情况,此时目标回波信号被设置的波门较好地接收;图 1b中给出了高重频干扰信号的特征,即重复频率越高,在时间轴上分布越密集;图 1c中给出了在高重频干扰场景下探测器设置波门录取回波信号时,部分干扰信号进入了接收波门内。

在特定漏射率、检测概率条件下,探测器连续观测到特定距离上N个发射信号的回波脉冲时,可认为成功捕获到目标,其中N与指示器漏射率、探测器目标检测概率等有关,在当前工艺下N为3或4,本文中取干扰方案中,通常将脉冲编码技术、时间波门技术、脉冲锁定技术这3种技术相结合来得到更好的抗干扰效果,如图 2所示。假设探测器接收到的首信号是激光目标指示器发射的第l个发射脉冲的回波,分析第l个~第l+3个发射脉冲的回波,目标回波序列为[1, 3, 6, 9]T,其中上标T表示向量的转置。由于高重频干扰信号超前于目标回波进入接收波门,接收波门内的首脉冲被干扰信号占据,接收下一个脉冲回波信号的实时波门向前偏移,导致在接收第l+3个脉冲时无法捕获目标回波7。根据首脉冲锁定技术,此时系统判定的目标回波序列[1, 2, 4, 6]T,而实际目标回波序列为[1, 3, 5, 7]T,此时表明高重频干扰信号已经成功干扰了制导系统。

在高重频情况下,干扰信号可能在目标回波信号之前就进入探测器接收波门,导致首个接收信号的可靠性下降。此时,以首脉冲为代表的传统脉冲锁定方法存在误判干扰信号的概率高以及易被牵引的问题。因此,在高重频干扰环境中,需要在波形设计、时间波门和信号处理技术方面开展端到端的优化。

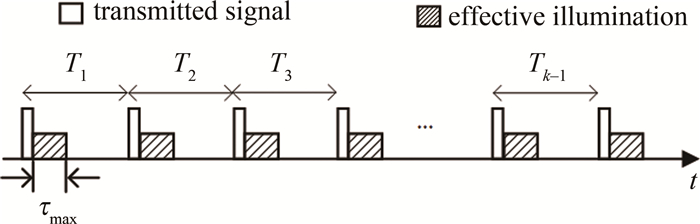

1.2 随机脉冲重复频率发射信号模型

激光目标指示器以随机重频方式发射信号,即脉冲周期为\boldsymbol{T}=\left[T_1, T_2, \cdots, T_{k-1}\right]^{\mathrm{T}},如图 3所示。激光目标指示器在工作时间内发射k个信号,可划分k-1个重复周期,定义Tk为第k-1个和第k个脉冲的重复周期,k取值范围为1≤k≤k-1,应有Tmin < Tk < Tmax,Tmin和Tmax分别为激光目标指示器发射信号的最小周期和最大周期,则激光指示器总的工作时间T_{\text {life }}=\sum\limits_{k=1}^{k-1} T_k。受传播损耗、目标散射特征、发射功率、探测器灵敏度等工程限制,通常情况下可探测回波最大时延τmax=2R/c≤Tmin,其中c为光速,R为有效探测距离。发射信号、脉冲重复周期、最大探测距离等参数如图 3所示。

假设发射脉冲信号波形为x(t),则发射波形为:

s_0(t)=\sum\limits_{k=0}^{k-1} x\left(t-t_k\right) (1) 式中: t_k=\sum\limits_{m=0}^k T_m,表示第k个脉冲相对第0个脉冲的发射迟延。第0个脉冲的发射时间为起始时间,T0=0。

1.3 干扰信号模型

当干扰机侦察到照射源发射信号时,干扰机发射高重频干扰信号以影响探测器效能,在高重频干扰场景下,探测器接收到的信号可以表示为:

s(t)=s_0{ }^{\prime}(t)+J(t)+n(t) (2) 式中: s0′(t)是发射脉冲信号对应的目标回波; J(t)为探测器接收到的干扰信号; n(t)为加性高斯白噪声。J(t)的表达式为:

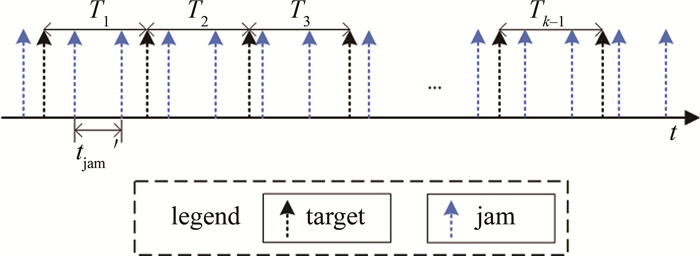

J(t)=\sum\limits_{i=1}^{\infty} A_i x\left(t-{\rm i} t_{\mathrm{jam}}{ }^{\prime}\right) (3) 式中:tjam′是高重频干扰信号重复周期; Ai是干扰机发射的第i个固定高重频干扰信号的幅度。此时探测器接收到的目标回波以及干扰信号如图 4所示。

在随机重频干扰场景下,接收机接收到的干扰信号的重复周期相较于固定重频干扰信号有随机抖动,此时J(t)的表达式为:

J(t)=\sum\limits_{i=1}^{\infty} A_i x\left(t-\mathrm{i} t_{\mathrm{jam}}{ }^{\prime}-\Delta t_i\right) (4) 式中: Δti为第i个随机重频干扰脉冲的随机时间抖动,传统的反向重频脉冲信号电路[19]无法有效对抗此类干扰。

式(2)中的n(t)为加性高斯白噪声,可看作是出现概率较低、且呈现时空随机分布的背景回波,会使探测器出现虚警,在影响机理上看,与距离随机的低重频干扰相似。由于本文中考虑了随机脉冲重复周期情况下高重频J(t)干扰,可以认为噪声n(t)为特定J(t)的一部分,其影响机理可以在大样本统计实验中包含。在后续的分析中,将略去n(t)项的影响。

2. 基于交叠波门的全脉冲回波探测及抗干扰方法

传统目标捕获方法常采用固定波门和单脉冲锁定技术[11],即每个脉冲回波的波门宽度相等,而且每一个发射脉冲接收波门按前一个接收波门检测到的某一信号为时间基准设置。该技术易出现波门被高重频干扰引偏而丢失目标问题。与此不同,自适应交叠波门则通过首脉冲确定下一脉冲接收波门的开启时刻,通过末脉冲确定下一脉冲接收波门的关闭时刻[20]。本文作者在参考文献[20]的基础上,采用自适应交叠波门技术,提出基于先验信息的信号判决方法,实现目标有效捕获和抗干扰技术。

2.1 自适应交叠波门的确定

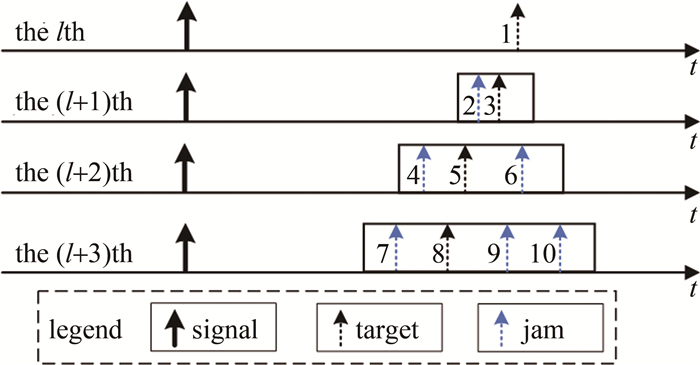

对脉冲重复周期为T=[T1, T2, …, Tk-1]T的发射激光序列,假设第l个脉冲的接收波门内接收到的首信号时间为ts,末信号的时间为te,则可以实时对第l+1个脉冲的波门进行设置:

\left\{\begin{array}{l} T_{\mathrm{g}, 1}=t_{\mathrm{s}}+\left(T_{l+1}-T_l\right)-\Delta t / 2 \\ T_{\mathrm{g}, 2}=t_{\mathrm{e}}+\left(T_{l+1}-T_l\right)+\Delta t / 2 \end{array}\right. (5) 式中: Tg, 1和Tg, 2是第l+1个脉冲实时波门的开启时刻和关闭时刻; Tl和Tl+1分别是第l个脉冲和第l+1个脉冲距离其下一个脉冲的脉冲重复周期; Δt是波门宽度,如图 5所示。

假设第l个脉冲发射之后,在第l个脉冲有效探测范围内接收到1号回波,以1号回波为基准时间,实时设置第l+1个脉冲的接收波门,并在此波门内接收到2、3号回波;以2号回波和3号回波为基准分别确定第l+2个脉冲接收波门的开启时刻和关闭时刻,并在此波门内接收到4、5、6号回波;以此递推下去,在第l+3个脉冲发射之后,探测器可以接收到7、8、9、10号回波,故将1号回波认为是疑似目标回波之后,通过自适应交叠波门得到的脉冲组合一共有4!=24种。接收机以接收4个发射脉冲的回波作为目标捕获的必要条件,在4个脉冲发射之后,在发射脉冲相对应的波门内收集到多组脉冲组合进入信号判决环节。

2.2 基于先验信息的信号判决

确定自适应交叠波门后,可以得到多个包含目标、干扰和噪声(如上文所述,噪声被看作干扰信号的一部分)的多个回波组合。由于发射脉冲时序T=[T1, T2, …, Tk-1]T已知, 通过编码先验信息和探测器运动特性,可以有效地排除固定重频干扰信号和随机重频干扰信号。

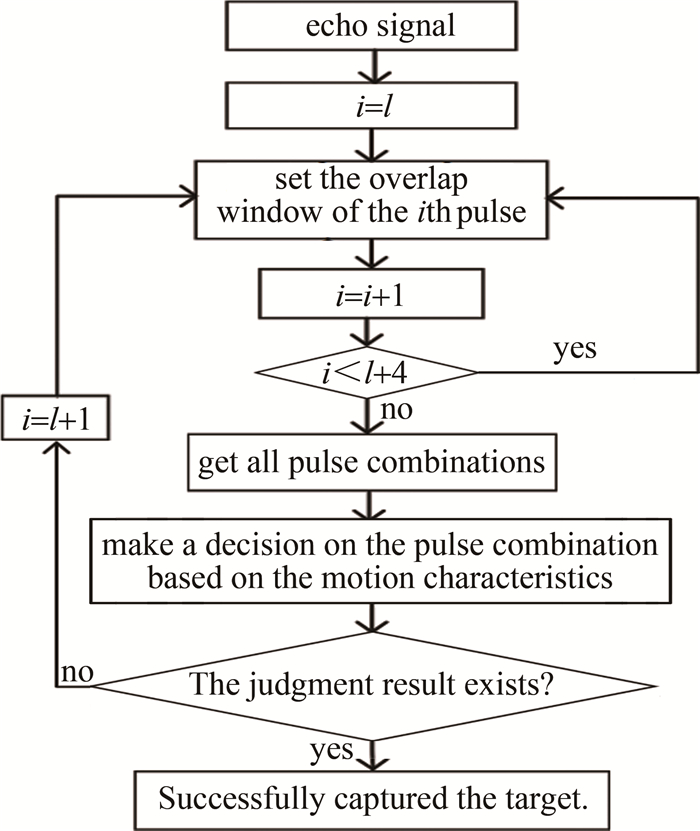

为简化问题,如第1.1节中所述,假定无干扰情况下,在4个接收波门中接收到至少3个满足时延特性的信号时, 可确认目标(具体探测脉冲数指标与漏设率、背景参数等决定,不是本文重点)。为不失一般性,假设打击目标静止不动,且激光目标指示器和探测器分别以2Ma的速度匀速飞向打击目标。假定某测试回波序列如图 5所示,此时的24种组合方式中,[1, 3, 5, 8]T组合是真实目标回波的组合,满足激光目标指示器和探测器运动特性,显然[1, 3, 6, 9]T不满足运动特性,可以直接鉴别为干扰组合。当有脉冲组合满足条件时,即可认为成功捕获到目标,否则回到目标捕获阶段,以第l+1个脉冲为起始判断脉冲,分析第l+1个脉冲至第l+4个脉冲的回波信号。算法流程图如图 6所示。

当接收到回波信号后,该算法依据激光探测器和激光目标指示器之间的时间同步关系,确定从第l个脉冲开始进行分析; 再根据发射脉冲先验信息及接收回波信号自适应生成第l个~第l+3个脉冲的交叠波门,以获得脉冲回波组合; 然后基于目标的运动特性对脉冲回波组合进行判决, 若判决结果符合运动规律,可以确定为已成功捕获目标;若未能捕获,则会将起始分析脉冲调整为第l+1个脉冲,并继续进行下一轮目标捕获。

2.3 性能评估指标

考虑到工程实际情况,设置激光目标指示器总工作时间Tlife=70 s,假定其从第l个脉冲开始检测回波信号后,判断第l个~第l+3个脉冲接收波门的回波信号是否为真实目标回波信号,为不失一般性,设置干扰信号与目标回波信号为01序列。

在仿真实验中,激光目标指示器和探测器的速率以680 m/s向目标移动,激光目标指示器的最大有效照射距离为25 km,激光漏射率为1‰,发射脉冲脉宽为10 ns,单个脉冲目标检测概率为98%,基础波门宽度为4 μs,各脉冲的自适应交叠波门由第2.1节中的算法得到。本文中随机生成了1200个重复频率均匀分布在20 Hz~30 Hz之间的发射脉冲信号,激光目标指示器按照生成的随机序列发射激光。全时段发射高重频干扰信号的干扰机位于目标的100 m处。

仿真生成与干扰信号混杂的目标回波信号,使用本文中算法对高重频干扰信号进行分析筛选,并计算出捕获到的目标的位置。当连续4个脉冲的回波信号符合运动规律时,即可认为目标捕获成功。为了验证本文中方法的性能,采用目标捕获时间(target acquisition time, TAT)指标进行性能评估,即:

T_{\mathrm{a}}=\sum\limits_{i=T_{\mathrm{s}}}^{T_{\mathrm{e}}} T_i (6) 式中: Ts为开始接收到目标回波的第1个脉冲间隔; Te为成功捕获到目标的最后一个脉冲间隔; Ta为捕获目标总消耗时间,Ta越小说明抗重频干扰算法性能越佳。

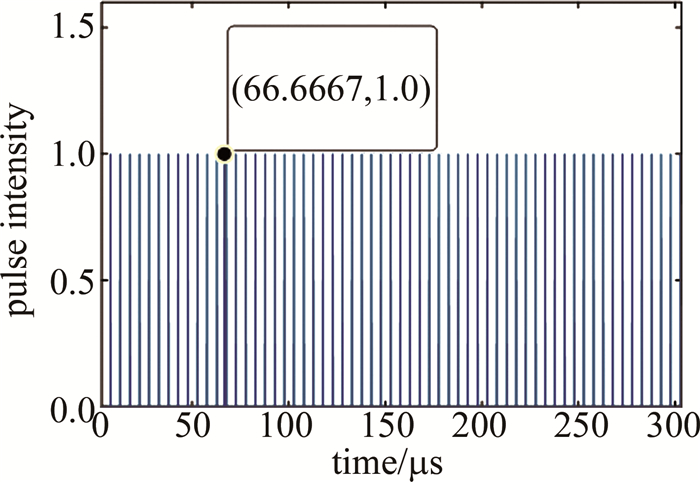

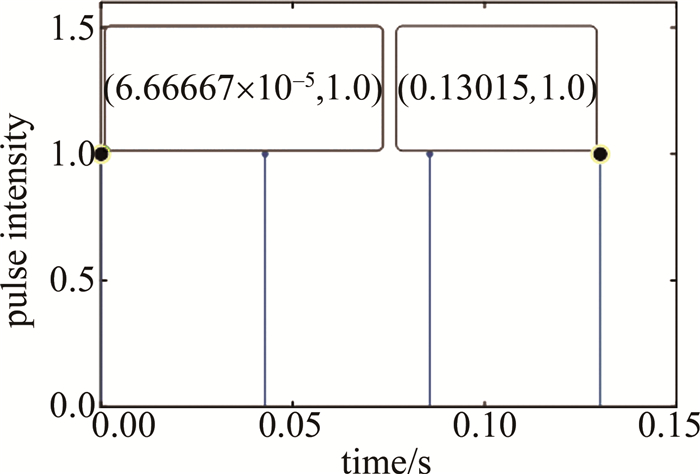

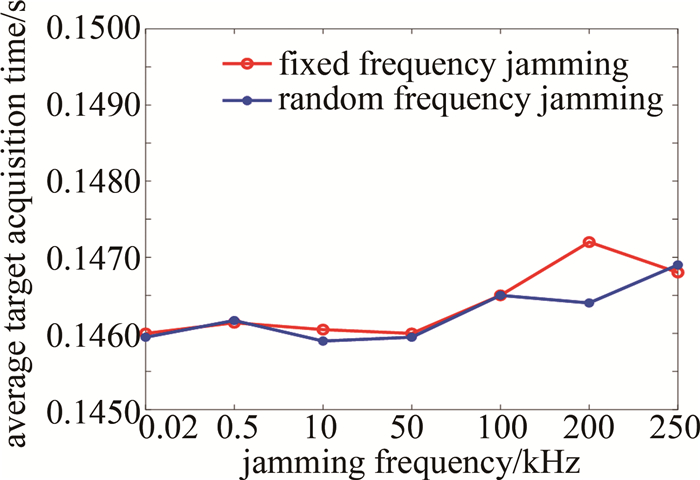

设激光目标指示器漏射率为1‰、检测概率为98%,干扰参数设置如表 1所示。共设置12种重频干扰仿真场景,其中随机重频干扰在固定重频干扰的基础上加了随机时间抖动, 仿真结果如图 7~图 9所示。图 7表示某一脉冲发射后受到200 kHz高重频干扰后,探测器接收到的回波信号,其中标注的信号为真实目标回波,对应目标距离探测器10 km;图 8表示利用本文中算法成功去除掉高重频干扰后,得到的真实目标回波脉冲组合,其起始时间为第45个脉冲的发射时间;图 9为在不同频率的固定重频干扰和随机重频干扰下各进行104次仿真实验的平均目标捕获时间。

表 1 干扰场景参数设置Table 1. Jamming scenario parameters configurationjamming types transmitted signal jamming frequency/kHz experiment fixed frequency random frequency distributed between 20 Hz~30 Hz 0.02, 0.5, 10, 100, 200, 250 10000 trials per frequency 由图 7和图 8可以看出,基于自适应交叠波门的全脉冲回波探测及抗干扰方法能够有效提取面对200 kHz的高重频干扰时目标的制导回波,并通过迟延计算确定当前目标与探测器的距离。图 9展示了不同频率干扰下目标平均捕获时间。实验结果表明,多种干扰场景下平均目标捕获时间均在0.146 s左右; 从低频到高频,目标平均捕获时间有轻微的提升; 多种干扰场景下平均目标捕获时间均小于0.2 s,这说明该算法能够在开始检测的前4个脉冲中捕获到真实目标回波的回波序列。

在多种干扰场景下的12×104次实验中,仿真结果未出现任何虚警情况,表明该算法具有良好的抗重频干扰性能。综上所述,本文中提出的抗干扰算法能够有效适应不同频率的固定重频干扰和随机重频干扰。

3. 结论

根据发射脉冲的编码规则,本文中设计了接收脉冲的自适应交叠波门,并利用探测器运动的先验信息对自适应交叠波门的接收信号进行了合理性判决。本文中的算法充分利用已知的随机脉冲规则与运动先验信息,分析连续N个脉冲接收波门的信号。由于N个脉冲对应的自适应交叠波门接收到的固定重频干扰信号以及随机重频干扰持续满足真实目标的回波规律的可能性极小,故此方法可以有效筛选去除干扰信号,对固定/随机重频干扰均具有较强的抗干扰性能。

在不同频率的固定/随机重频干扰场景下,利用仿真实验验证了本文中算法的有效性和优越性。仿真结果表明,在干扰场景下,随机重频激光制导雷达抗高重频干扰技术不仅可以成功捕获目标,而且目标捕获时间与无干扰场景下的捕获时间相当,保证了捕获目标的时效性,并且在12×104次统计试验中未出现虚警问题。此算法的优越性在于: 在高重频干扰环境下仍然具备高探测概率和低虚警概率,可用于提高激光制导雷达系统的抗干扰能力,提高其工作效率和可靠性。

-

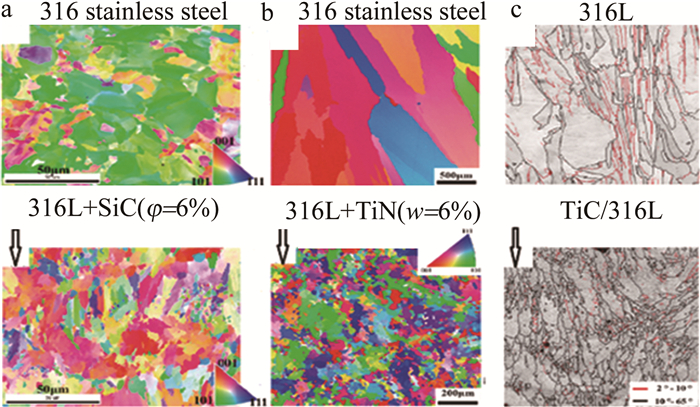

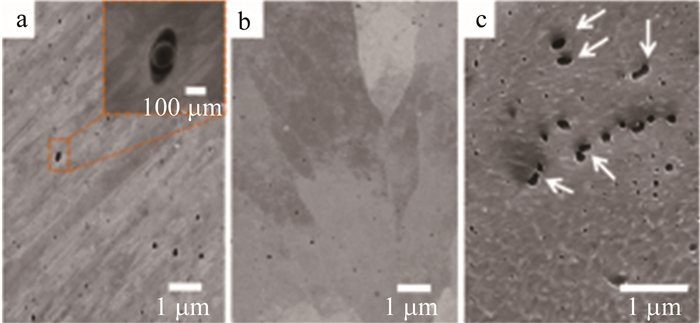

图 7 a—LPBF成型的316L和316L+SiC/316L的彩色反极图[13] b—LPBF成型的316L和316L+ TiN/316L的彩色反极图[30] c—316L和TiC/316L的微观结构[31]

Figure 7. a—inverse pole figure of LPBF samples of 316L and SiC/316L[13] b—inverse pole figure of LPBF samples of 316L and TiN/316L[30] c—microstructure characterization of 316L and TiC/316L[31]

表 1 纳米颗粒增强LPBF成型奥氏体不绣钢的力学性能

Table 1 Mechanical properties of LPBF built austenitic stainless steel reinforced by nano-particle

stainless steel nano-particle grain size/μm ρ/% room temperature tensile strength ε/% reference stainless steel nanoparticle σs/MPa σe/MPa 316 SiC 13.3 9.4 >99.3 996±25 1301±37 5.1~14 [13] 316L TiC 28.18 6.99 98.22 712~811.5 — — [14] 316L TiB2 — 1.67~5.71 99.8 827.5~980.9 — — [15] 304L Y2O3 8.2±5.3 8.1±4.8 — 575±8 700±13 32±5 [16] 316 graphene 21.0 15.6 — — 738 38 [25] 316L Al2O3 79 25 98 579±9.7 662±3.18 — [28] 316L CeO2 45±3 25±2 99.9 485±4 — — [24] 316L TiN 11.2 3.5~7.5 — 629~640 — 26~30 [30] 316L Y2O3 8 10~70 99.3~99.4 574 — 90.5 [33] 316L Nb and C — 10~12 99.7 580 700 35 [34] -

[1] FRAZIER W E. Metal additive manufacturing: A review[J]. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance, 2014, 23(6): 1917-1928. DOI: 10.1007/s11665-014-0958-z

[2] GU D, MEINERS W, WISSENBACH K, et al. Laser additive manufacturing of metallic components: Materials, processes and mechanisms[J]. International Materials Reviews, 2012, 57(3): 133-164. DOI: 10.1179/1743280411Y.0000000014

[3] GHAYOOR M, LEE K, HE Y, et al. Selective laser melting of 304L stainless steel: Role of volumetric energy density on the microstructure, texture and mechanical properties[J]. Additive Manufacturing, 2020, 32(5): 101011.

[4] 李俊辉, 任维彬, 任玉中, 等. 钛合金部件激光再制造材料与工艺研究进展[J]. 激光技术, 2023, 47(3): 353-359. DOI: 10.7510/jgjs.issn.1001-3806.2023.03.011 LI J H, REN W B, REN Y Zh, et al. Research progress of laser remanufacturing materials and processes for titanium alloy parts[J]. Laser Technology, 2023, 47(3): 353-359(in Chinese). DOI: 10.7510/jgjs.issn.1001-3806.2023.03.011

[5] WANG Y M, VOISIN T, MCKEOWN J T, et al. Additively manufactured hierarchical stainless steels with high strength and ductility[J]. Nature Materials, 2017, 17(1): 63-71.

[6] ABOULKHAIR N T, SIMONELLI M, PARRY L, et al. 3D printing of aluminium alloys: Additive manufacturing of aluminium alloys using selective laser melting[J]. Progress in Materials Science, 2019, 106: 100578. DOI: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2019.100578

[7] TOLOSA I, GARCIANDÍA F, ZUBIRI F, et al. Study of mechanical properties of AISI316 stainless steel processed by "selective laser melting", following different manufacturing strategies[J]. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 2010, 51(5): 639-647.

[8] ROTTGER A, GEENEN K, WINDMANN M, et al. Comparison of microstructure and mechanical properties of 316L austenitic steel processed by selective laser melting with hot-isostatic pressed and cast material[J]. Materials Science and Engineering, 2016, A678: 365-376.

[9] MERTENS A, REGINSTER S, CONTREPOIS Q, et al. Microstructures and mechanical properties of stainless steel AISI 316L processed by selective laser melting[J]. Materials Science Forum, 2014, 783/786: 898-903.

[10] GUAN K, WANG Z, GAO M, et al. Effects of processing parameters on tensile properties of selective laser melted 304 stainless steel[J]. Materials & Design, 2013, 50(9): 581-586.

[11] NGUYEN Q B, ZHU Z, NG F L, et al. High mechanical strengths and ductility of stainless steel 304L fabricated using selective laser melting[J]. Journal of Materials Science and Technology, 2018, 35(2): 388-394.

[12] WANG Z Q, PALMER T A, BEESE A M. Effect of processing parameters on microstructure and tensile properties of austenitic stainless steel 304L made by directed energy deposition additive manufacturing[J]. Acta Materialia, 2016, 110: 226-235. DOI: 10.1016/j.actamat.2016.03.019

[13] ZOU Y, TAN C, QIU Z, et al. Additively manufactured SiC-reinforced stainless steel with excellent strength and wear resistance[J]. Additive Manufacturing, 2021, 41 (1): 101971.

[14] ALMANGOUR B, BAEK M S, GRZESIAK D, et al. Strengthening of stainless steel by titanium carbide addition and grain refinement during selective laser melting[J]. Materials Science & Engineering, 2018, A712: 812-818.

[15] ALMANGOUR B, GRESIAK D, YANG J M. Rapid fabrication of bulk-form TiB2/316L stainless steel nanocomposites with novel reinforcement architecture and improved performance by selective laser melting[J]. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2016, 680: 480-493. DOI: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.04.156

[16] GHAYOOR M, LEE K, HE Y, et al. Selective laser melting of 304L austenitic oxide dispersion strengthened steel: Processing, microstructural evolution and strengthening mechanisms[J]. Materials Science Engineering, 2020, A788: 139532.

[17] FISCHER P, ROMANO V, WEBER H P, et al. Sintering of commercially pure titanium powder with a Nd∶YAG laser source[J]. Acta Materialia, 2003, 51(6): 1651-1662. DOI: 10.1016/S1359-6454(02)00567-0

[18] ALMANGOUR B, GRZESIAK D, BORKAR T, et al. Densification behavior, microstructural evolution, and mechanical properties of TiC/316L nanocomposites fabricated by selective laser melting[J]. Materials Design, 2017, 138: 119-128.

[19] ZHOU X, de HOSSON J T M. Reactive wetting of liquid metals on ceramic substrates[J]. Acta Materialia, 1996, 44(2): 421-426. DOI: 10.1016/1359-6454(95)00235-9

[20] TAKAMICHI I, RODERICK I G. The physical properties of liquid metals[M]. Cambridge, UK: Clarendon Press, 1993: 48-56.

[21] SIMCHI A. Direct laser sintering of metal powders: Mechanism, kinetics and microstructural features[J]. Materials Science and Engineering, 2006, A428(1/2): 148-158.

[22] SIMCHI A, POHL H. Direct laser sintering of iron-graphite powder mixture[J]. Materials Science and Engineering, 2004, A383(2): 191-200.

[23] SAEIDI K, GAO X, ZHONG Y, et al. Hardened austenite steel with columnar subgrain structure formed by laser melting[J]. Materials Science and Engineering, 2015, A625: 221-229.

[24] SALMAN O O, FUNK A, WASKE A, et al. Additive manufacturing of a 316L steel matrix composite reinforced with CeO2 particles: Process optimization by adjusting the laser scanning speed[J]. Technologies, 2018, 6(1): 25. DOI: 10.3390/technologies6010025

[25] HAN Y, ZHANG Y, JING H, et al. Selective laser melting of low-content graphene nanoplatelets reinforced 316L austenitic stainless steel matrix: Strength enhancement without affecting ductility[J]. Additive Manufacturing, 2020, 34(8): 101381.

[26] SIMCHI A, PETZOLDT F, POHL H. Direct metal laser sintering: Material considerations and mechanisms of particle bonding[J]. International Journal of Powder Metallurgy, 2001, 37(2): 49-61.

[27] NIENDORF T, LEUDERS S, RIEMER A, et al. Highly anisotropic steel processed by selective laser melting[J]. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions, 2013, B44(4): 794-799.

[28] LI X, WILLY H J, CHANG S, et al. Selective laser melting of stainless steel and alumina composite: Experimental and simulation studies on processing parameters, microstructure and mechanical properties[J]. Materials and Design, 2018, 145: 1-10.

[29] TAN C, ZHOU K, KUANG M, et al. Microstructural characterisation and properties of selective laser melted maraging steel with different build directions[J]. Science and Technology of Advanced Materials, 2018, 19(1): 746-758.

[30] WANG Y, LIU Z H, ZHOU Y Z, et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of TiN particles strengthened 316L steel prepared by laser melting deposition process[J]. Materials Science and Engineering, 2021, A814: 141220.

[31] ZHANG X Y, ZHONG J, GUO S L, et al. Control of deformation and annealing process to produce incoherent Σ3 boundaries in Hastelloy C-276 alloy[J]. Nuclear Materials and Energy, 2021, 27: 100944.

[32] LI J, QU H, BAI J. Grain boundary engineering during the laser powder bed fusion of TiC/316L stainless steel composites: New mechanism for forming TiC-induced special grain boundaries[J]. Acta Materialia, 2022, 226: 117605.

[33] ZHONG Y, LIU L, ZOU J, et al. Oxide dispersion strengthened stainless steel 316L with superior strength and ductility by selective laser melting[J]. Journal of Materials Science Technology, 2020, 42(1): 97-105.

[34] DRYEPONDT S, NANDWANA P, UNOCIC K A, et al. High temperature high strength austenitic steel fabricated by laser powder-bed fusion[J]. Acta Materialia, 2022, 231: 117876.

[35] WANG D, SONG C, YANG Y, et al. Investigation of crystal growth mechanism during selective laser melting and mechanical property characterization of 316L stainless steel parts[J]. Materials Design, 2016, 100: 291-299.

[36] GU D, WANG H, DAI D, et al. Rapid fabrication of Al-based bulk-form nanocomposites with novel reinforcement and enhanced performance by selective laser melting[J]. Scripta Materialia, 2015, 96(1): 25-28.

[37] ABRAMOVA M, ENIKEEV N, VALIEV R, et al. Grain boundary segregation induced strengthening of an ultrafine-grained austenitic stainless steel[J]. Materials Letters, 2014, 136: 349-352.

[38] WANG Y M, VOISIN T, MCKEOWN J T, et al. Additively manufactured hierarchical stainless steels with high strength and ductility[J]. Natuer Materials, 2018, 17(1): 63-71.

[39] NGUYEN Q B, ZHU Z, NG F L, et al. High mechanical strengths and ductility of stainless steel 304L fabricated using selective laser melting[J]. Journal of Materials Science Technology, 2019, 35(2): 388-394.

[40] KONG D, DONG C, NI X, et al. Mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of selective laser melted 316L stainless steel after different heat treatment processes[J]. Journal of Materials Science Technology, 2019, 35(7): 1499-1507.

下载:

下载: